Albert Einstein was a racist Zionist. He believed that anti-Semitism was good for the Jewish "race" because it promoted segregation and separated Jews from the, to use his word, "Goyim". John Stachel wrote,

"While he lived in Germany, however, Einstein seems to have accepted the then-prevalent racist mode of thought, often invoking such concepts as 'race' and 'instinct,' and the idea that the Jews form a race."— J. Stachel, "Einstein's Jewish Identity", Einstein from 'B' to 'Z', Birkhaeuser, Boston, Basel, Berlin, (2002), pp. 57-83, at 68.

Einstein helped Hitler and the Zionist Nazis by promoting the belief among Jews that anti-Semitism was the Jews' salvation. Einstein stated,

"I am neither a German citizen, nor is there in me anything that can be described as 'Jewish faith.' But I am happy to belong to the Jewish people, even though I don't regard them as the Chosen People. Why don't we just let the Goy keep his anti-Semitism, while we preserve our love for the likes of us?"—A. Einstein quoted in A. Foelsing, English translation by E. Osers, Albert Einstein, a Biography, Viking, New York, (1997), p. 494; which cites speech to the Central-Verein Deutscher Staatsbuerger Juedischen Glaubens, in Berlin on 5 April 1920, in D. Reichenstein, Albert Einstein. Sein Lebensbild und seine Weltanschauung, Berlin, (1932). This letter from Einstein to the Central Association of German Citizens of the Jewish Faith of 5 April 1920 is reproduced in The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Volume 9, Document 368, Princeton University Press, (2004).

Einstein also stated,

"The way I see it, the fact of the Jews' racial peculiarity will necessarily influence their social relations with non-Jews. The conclusions which—in my opinion—the Jews should draw is to become more aware of their peculiarity in their social way of life and to recognize their own cultural contributions. First of all, they would have to show a certain noble reservedness and not be so eager to mix socially—of which others want little or nothing. On the other hand, anti-Semitism in Germany also has consequences that, from a Jewish point of view, should be welcomed. I believe German Jewry owes its continued existence to anti-Semitism."—Albert Einstein, A. Engel translator, "How I became a Zionist", The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Volume 7, Document 57, Princeton University Press, (2002), pp. 234-235, at 235.

Einstein stated,

"Anti-Semitism will be a psychological phenomenon as long as Jews come in contact with non-Jews—what harm can there be in that? Perhaps it is due to anti-Semitism that we survive as a race: at least that is what I believe."—Albert Einstein, English translation by A. Engel, The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Volume 7, Document 37, Princeton University Press, (2002), p. 159.

Einstein was not an original thinker. In fact, Einstein was an habitual and psychopathic plagiarist. His dreadful views on "race" and segregation were first iterated by such prominent Jews as Spinoza and Theodor Herzl. They were cliches among racist Zionists.

In 1896, racist Zionist Theodor Herzl wrote his widely read book The Jewish State,

"Great exertions will not be necessary to spur on the movement. Anti-Semites provide the requisite impetus. They need only do what they did before, and then they will create a love of emigration where it did not previously exist, and strengthen it where it existed before. [***] I imagine that Governments will, either voluntarily or under pressure from the Anti-Semites, pay certain attention to this scheme; and they may perhaps actually receive it here and there with a sympathy which they will also show to the Society of Jews."— T. Herzl, A Jewish State: An Attempt at a Modern Solution of the Jewish Question, The Maccabaean Publishing Co., New York, (1904), pp. 68, 93.

Einstein stated in 1938,

"JUST WHAT IS A JEW?

The formation of groups has an invigorating effect in all spheres of human striving, perhaps mostly due to the struggle between the convictions and aims represented by the different groups. The Jews, too, form such a group with a definite character of its own, and anti-Semitism is nothing but the antagonistic attitude produced in the non-Jews by the Jewish group. This is a normal social reaction. But for the political abuse resulting from it, it might never have been designated by a special name.

What are the characteristics of the Jewish group? What, in the first place, is a Jew? There are no quick answers to this question. The most obvious answer would be the following: A Jew is a person professing the Jewish faith. The superficial character of this answer is easily recognized by means of a simple parallel. Let us ask the question: What is a snail? An answer similar in kind to the one given above might be: A snail is an animal inhabiting a snail shell. This answer is not altogether incorrect; nor, to be sure, is it exhaustive; for the snail shell happens to be but one of the material products of the snail. Similarly, the Jewish faith is but one of the characteristic products of the Jewish community. It is, furthermore, known that a snail can shed its shell without thereby ceasing to be a snail. The Jew who abandons his faith (in the formal sense of the word) is in a similar position. He remains a Jew.

WHERE OPPRESSION IS A STIMULUS

[***]

Perhaps even more than on its own tradition, the Jewish group has thrived on oppression and on the antagonism it has forever met in the world. Here undoubtedly lies one of the main reasons for its continued existence through so many thousands of years."—A. Einstein, "Why do They Hate the Jews?", Collier's, Volume 102, (26 November 1938); reprinted in Ideas and Opinions, Crown, New York, (1954), pp. 191-198, at 194, 196. Einstein expressed himself in a similar way to Peter A. Bucky, P. A. Bucky, Einstein, and A. G. Weakland, The Private Albert Einstein, Andrews and McMeel, Kansas City, (1992), p. 87.

Albert Einstein was parroting racist political Zionist leader Theodor Herzl, who wrote in his book The Jewish State,

"Oppression and persecution cannot exterminate us. No nation on earth has survived such struggles and sufferings as we have gone through. Jew-baiting has merely stripped off our weaklings; the strong among us were invariably true to their race when persecution broke out against them. This attitude was most clearly apparent in the period immediately following the emancipation of the Jews. Later on, those who rose to a higher degree of intelligence and to a better worldly position lost their communal feeling to a very great extent. Wherever our political well-being has lasted for any length of time, we have assimilated with our surroundings. I think this is not discreditable. Hence, the statesman who would wish to see a Jewish strain in his nation would have to provide for the duration of our political well-being; and even Bismarck could not do that. [***] The Governments of all countries scourged by Anti-Semitism will serve their own interests in assisting us to obtain the sovereignty we want. [***] Great exertions will not be necessary to spur on the movement. Anti-Semites provide the requisite impetus. They need only do what they did before, and then they will create a love of emigration where it did not previously exist, and strengthen it where it existed before. [***] I imagine that Governments will, either voluntarily or under pressure from the Anti-Semites, pay certain attention to this scheme; and they may perhaps actually receive it here and there with a sympathy which they will also show to the Society of Jews."—T. Herzl, A Jewish State: An Attempt at a Modern Solution of the Jewish Question, The Maccabaean Publishing Co., New York, (1904), pp. 5-6, 25, 68, 93.

In 1938, Einstein stated in his essay "Our Debt to Zionism",

"Rarely since the conquest of Jerusalem by Titus has the Jewish community experienced a period of greater oppression than prevails at the present time. [***] Yet we shall survive this period too, no matter how much sorrow, no matter how heavy a loss in life it may bring. A community like ours, which is a community purely by reason of tradition, can only be strengthened by pressure from without."—A. Einstein, "Our Debt to Zionism", Out of My Later Years, Carol Publishing Group, New York, (1995), pp. 262-264, at 262.

Theodor Herzl wrote,

"What would you say, for example, if I did not deny there are good aspects of anti-Semitism? I say that anti-Semitism will educate the Jews. In fifty years, if we still have the same social order, it will have brought forth a fine and presentable generation of Jews, endowed with a delicate, extremely sensitive feeling for honor and the like."—Theodor Herzl, as quoted by Amos Elon, Herzl, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York, (1975), pp. 114-115.

Herzl wrote in his diary,

"the Pressburg anti-Semite Ivan von Simonyi [***] Loves me!"—T. Herzl, English translation by H. Zohn, R. Patai, Editor, The Complete Diaries of Theodor Herzl, Volume 1, Herzl Press, New York, (1960), p. 317.

Herzl also stated,

"In the beginning we shall be supported by anti-Semites through a recrudescence* of persecution (for I am convinced that they do not expect success and will want to exploit their 'conquest.')"—T. Herzl, English translation by H. Zohn, R. Patai, Editor, The Complete Diaries of Theodor Herzl, Volume 1, Herzl Press, New York, (1960), p. 56.

Herzl believed,

"The anti-Semites will become our most dependable friends, the anti-Semitic countries our allies."—T. Herzl, English translation by H. Zohn, R. Patai, Editor, The Complete Diaries of Theodor Herzl, Volume 1, Herzl Press, New York, (1960), p. 84.

Herzl declared the virtue and justice, in his racist mind, of anti-Semitism,

"[W]e want to let respectable anti-Semites participate in our project [***] Present-day anti-Semitism can only in a very few places be taken for the old religious intolerance. For the most part it is a movement among civilized nations whereby they try to exorcize a ghost from out of their own past. [***] The anti-Semites will have carried the day. Let them have this satisfaction, for we too shall be happy. They will have turned out to be right because they are right. They could not have let themselves be subjugated by us in the army, in government, in all of commerce, as thanks for generously having let us out of the ghetto. Let us never forget this magnanimous deed of the civilized nations. [***] Thus, anti-Semitism, too, probably contains the divine Will to Good, because it forces us to close ranks, unites us through pressure, and through our unity will make us free."— T. Herzl, English translation by H. Zohn, R. Patai, Editor, The Complete Diaries of Theodor Herzl, Volume 1, Herzl Press, New York, (1960), pp. 143, 171, 182, 231.

In 1897, Herzl told the First Zionist Congress,

"The feeling of communion, of which we have been so bitterly accused, had commenced to weaken when anti-Semitism attacked us. Anti-Semitism has restored it. We have, so to speak, gone home. Zionism is the return home of Judaism even before the return to the land of the Jews."—"The Zionist Congress: Full Report of the Proceedings", The Jewish Chronicle, (3 September 1897), pp. 10-15, at 11.

Racist Zionist Max Nordau wrote in 1905,

"Anti-Semitism has also taught many educated Jews the way back to their people."—M. Nordau and G. Gottheil, Zionism and Anti-Semitism, Fox, Duffield & Company, (1905), p. 19.

Like Herzl, Einstein stated that Jews exercised undue influence in Germany. Einstein wrote in the Juedische Rundschau, on 21 June 1921, on pages 351-352,

"This phenomenon [i. e. Anti-Semitism] in Germany is due to several causes. Partly it originates in the fact that the Jews there exercise an influence over the intellectual life of the German people altogether out of proportion to their number. While, in my opinion, the economic position of the German Jews is very much overrated, the influence of Jews on the Press, in literature, and in science in Germany is very marked, as must be apparent to even the most superficial observer. This accounts for the fact that there are many anti-Semites there who are not really anti-Semitic in the sense of being Jew-haters, and who are honest in their arguments. They regard Jews as of a nationality different from the German, and therefore are alarmed at the increasing Jewish influence on their national entity. [***] But in Germany the judgement of my theory depended on the party politics of the Press[.]"—A. Einstein, "Jewish Nationalism and Anti-Semitism", The Jewish Chronicle, (17 June 1921), p. 16.

Einstein's Jewish racism made him disloyal to Germany and treacherous. On 8 July 1901, Einstein wrote,

"There is no exaggeration in what you said about the German professors. I have got to know another sad specimen of this kind — one of the foremost physicists of Germany."—A. Einstein to J. Winteler, English translation by A. Beck, The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Volume 1, Document 115, Princeton University Press, (1987), pp. 176-177, at 177.

Einstein wrote sometime after 1 January 1914,

"A free, unprejudiced look is not at all characteristic of the (adult) Germans (blinders!)."—A. Einstein, English translation by A. Beck, The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Volume 5, Document 499, Princeton University Press, (1995), pp. 373-374, at 374.

After the First World War, Einstein and some of his friends alluded to much earlier conversations with Einstein, where he had correctly predicted the eventual outcome of the war. In his diaries, Romain Rolland recorded his conversations with Einstein in Switzerland at their meeting of 16 September 1915,

"What I hear from [Einstein] is not exactly encouraging, for it shows the impossibility of arriving at a lasting peace with Germany without first totally crushing it. Einstein says the situation looks to him far less favorable than a few months back. The victories over Russia have reawakened German arrogance and appetite. The word 'greedy' seems to Einstein best to characterize Germany. [***] Einstein does not expect any renewal of Germany out of itself; it lacks the energy for it, and the boldness for initiative. He hopes for a victory of the Allies, which would smash the power of Prussia and the dynasty. . . . Einstein and Zangger dream of a divided Germany—on the one side Southern Germany and Austria, on the other side Prussia. [***] We speak of the deliberate blindness and the lack of psychology in the Germans."—R. Romain, La Conscience de l'Europe, Volume 1, pp. 696ff. English translation from A. Foelsing, Albert Einstein: A Biography, Viking, New York, (1997), pp. 365-367. See also:The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Volume 8, Document 118, Princeton University Press, (1998); andThe Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Volume 8, Document 374, Princeton University Press, (1998).

Letter from A. Einstein to R. Romain of 15 September 1915, Letter from A. Einstein to R. Romain of 22 August 1917,

Jews often sought to Balkanize nations so as to weaken the power of any faction within a nation and to create perpetual agitation between the nations which could be exploited for profit and other Jewish gains. For example, the Rothschilds created the American Civil War and profited from the debts it generated. They hoped to divide America into two nations and to pit these against one another. They were successful. Jews had long been pitting North German Protestants against South German and Austrian Catholics. Jews were the motive force behind the Kulturkampf. After creating these divides and promoting perpetual agitations amongst neighbors, Jewry could then fund one side against the other to destroy it whenever Jewry decided to wreck a given nation.

Einstein's dreams during the First World War remind one of the "Carthaginian Peace" of the Henry Morgenthau, Jr. plan for the destruction of Germany following the Second World War. Morgenthau worked with Lord Cherwell (Frederick Alexander Lindemann), Churchill's friend and advisor, who planned to bomb German civilian populations into submission. Lindemann studied under Einstein's friend, Walther Nernst, who worked with Fritz Haber, a Jewish developer of poisonous gas. James Bacque argues that the Allies, under the direction of General Eisenhower, starved hundreds of thousands, if not millions of German prisoners of war to death. [J. Bacque, Other Losses: An Investigation into the Mass Deaths of German Prisoners at the Hands of the French and Americans after World War II, Stoddart,Toronto, (1989).]

Einstein often spoke in genocidal and racist terms against Germany, and for the Jews and England, and he betrayed Germany before, during and after the war. Einstein's Jewish treachery and that of other such Jewish traitors as Georg Bernhard, Theodor Wolff and Maximilian Harden, who "stabbed Germany in the back" during and after World War I, led to Hitler's rise to power. Einstein wrote to Paul Ehrenfest on 22 March 1919,

"[The Allied Powers] whose victory during the war I had felt would be by far the lesser evil are now proving to be only slightly the lesser evil. [***] I get most joy from the emergence of the Jewish state in Palestine. It does seem to me that our kinfolk really are more sympathetic (at least less brutal) than these horrid Europeans. Perhaps things can only improve if only the Chinese are left, who refer to all Europeans with the collective noun 'bandits.'"—Letter from A. Einstein to Paul Ehrenfest of 22 March 1919, English translation by A. Hentschel, The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Volume 9, Document 10, Princeton Univsersity Press, (2004), pp. 9-10, at 10.

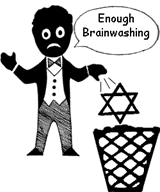

While responsible people were trying to preserve some sanity in the turbulent period following World War I, racist Zionists including Albert Einstein sought to validate and encourage the racism of anti-Semites. The Dreyfus Affair taught them that anti-Semitism had a powerful effect to unite Jews around the world.

The Zionists were afraid that the "Jewish race" was disappearing through assimilation. They wanted to use anti-Semitism to force the segregation of Jews from Gentiles and to unite Jews, and thereby preserve the "Jewish race". They hoped that if they put a Hitler-type into power—as Zionists had done in the past, they could use him to herd up the Jews of Europe and force these Jews into Palestine against their will. This would also help the Zionists to inspire distrust of, and contempt for, Gentile government, while giving the Zionists the moral high-ground in international affairs, despite the fact that the Zionists were secretly behind the atrocities.

Albert Einstein wrote to Max Born on 9 November 1919. In this letter, Einstein encouraged anti-Semitism and advocated segregation (one must wonder what role Albert's increasing racism played in his divorce from Mileva Maric, who was a Gentile Serb whom Einstein's racist mother hated),

"Antisemitism must be seen as a real thing, based on true hereditary qualities, even if for us Jews it is often unpleasant. I could well imagine that I myself would choose a Jew as my companion, given the choice. On the other hand I would consider it reasonable for the Jews themselves to collect the money to support Jewish research workers outside the universities and to provide them with teaching opportunities."—M. Born, The Born-Einstein Letters, Walker and Company, New York, (1971), p. 16.

In 1933, the Zionists publicly declared their allegiance to the Nazis. They wrote in the Juedische Rundshau on 13 June 1933,

"Zionism recognizes the existence of the Jewish question and wants to solve it in a generous and constructive manner. For this purpose, it wants to enlist the aid of all peoples; those who are friendly to the Jews as well as those who are hostile to them, since according to its conception, this is not a question of sentimentality, but one dealing with a real problem in whose solution all peoples are interested."—English translation in: K. Polkehn, "The Secret Contacts: Zionism and Nazi Germany, 1933-1941", Journal of Palestine Studies, Volume 5, Number 3/4, (Spring-Summer, 1976), pp. 54-82, at 59.

On 21 June 1933, the Zionists issued a declaration of their position with respect to the Nazi regime, in which they expressed a belief in the legitimacy of the Nazis' racist belief system and condemned anti-Fascist forces. [See: L. S. Dawidowicz, "The Zionist Federation of Germany Addresses the New German State", A Holocaust Reader, Behrman House, Inc., West Orange, New Jersey, (1976), pp. 150-155. See also: H. Tramer, Editor, S. Moses, In zwei Welten: Siegfried Moses zum fuenfundsiebzigsten Geburtstag, Verlag Bitaon, Tel-Aviv, (1962), pp. 118.ff; cited in K. Polkehn, "The Secret Contacts: Zionism and Nazi Germany, 1933-1941", Journal of Palestine Studies, Volume 5, Number 3/4, (Spring-Summer, 1976), pp. 54-82, at 59.]

Einstein's close friend and collaborator Michele Besso wrote that it might have been Albert Einstein's racism and bigotry which caused him to separate from his first wife Mileva Maric in 1914. Besso wrote to Einstein on 17 January 1928,

"[. . .]perhaps it is due in part to me, with my defense of Judaism and the Jewish family, that your family life took the turn that it did, and that I had to bring Mileva from Berlin to Zurich[.]"—English translation quoted from J. Stachel, "Einstein's Jewish Identity", Einstein from 'B' to 'Z', Birkhaeuser, Boston, Basel, Berlin, (2002), pp. 57-83, at 78. Stachel cites M. Besso, A. Einstein, Correspondance, 1903-1955, Hermann, Paris, (1972), p. 238.

The hypocrisy of racist Zionists often manifested itself. Einstein was but one of many racist Zionist Jews who married a Gentile. As another example, consider the fact that racist Zionist Moses Hess was married to a Christian Gentile prostitute named Sybille Pritsch.

Einstein may have been affected by his mother's early racist opposition to his relationship with Maric. Another factor in the Einsteins' divorce was, of course, Albert's incestuous relationship with his cousin Else Einstein, and his desire to bed her daughters, as well as Albert's general promiscuity—some believe he was a syphilitic whore monger.

Albert Einstein opposed his sister Maja's marriage to the Gentile Paul Winteler on racist grounds and thought that they should divorce. Albert Einstein wrote to Michele Besso on 12 December 1919 and stated that,

"No mixed marriages are any good (Anna says: oh!)"—Letter from A. Einstein to M. Besso of 12 December 1919, English translation by A. Hentschel, The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Volume 9, Document 207, Princeton University Press, (2004), pp. 178-179, at 179.

Besso was married to a Gentile, Anna Besso-Winteler. Denis Brian wrote,

"When asked what he thought of Jews marrying non-Jews, which, of course, had been the case with him and Mileva, [Albert Einstein] replied with a laugh, 'It's dangerous, but then all marriages are dangerous.'"—D. Brian, The Unexpected Einstein: The Real Man Behind the Icon, Wiley, Hoboken, New Jersey, (2005), p. 42.

On 3 April 1920, Einstein wrote, criticizing assimilationist Jews,

"And this is precisely what he does not want to reveal in his confession. He talks about religious faith instead of tribal affiliation, of 'Mosaic' instead of 'Jewish' because the latter term, which is much more familiar to him, would emphasize affiliation to his tribe."—A. Einstein, English translation by A. Engel, The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Volume 7, Document 34, Princeton University Press, (2002), pp. 153-155, at 153.

After declaring that Jewish children segregate due to natural forces and that they are "different from other children", not due to religion or tradition, but due to genetic features and "heritage", Einstein continued his 3 April 1920 statement,

"With adults it is quite similar as with children. Due to race and temperament as well as traditions (which are only to a small extent of religious origin) they form a community more or less separate from non-Jews. [***] It is this basic community of race and tradition that I have in mind when I speak of 'Jewish nationality.' In my opinion, aversion to Jews is simply based upon the fact that Jews and non-Jews are different. [***] Where feelings are sufficiently vivid there is no shortage of reasons; and the feeling of aversion toward people of a foreign race with whom one has, more or less, to share daily life will emerge by necessity."—A. Einstein, English translation by A. Engel, The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Volume 7, Document 34, Princeton University Press, (2002), pp. 153-155, at 153-154.

Einstein made similar comments in a document dated sometime "after 3 April 1920". Einstein was in agreement with Philipp Lenard that a "Jewish heritage" (read for "heritage", "racial instinct") could be seen in intellectual works published by Jews. Einstein stated,

"The psychological root of anti-Semitism lies in the fact that the Jews are a group of people unto themselves. Their Jewishness is visible in their physical appearance, and one notices their Jewish heritage in their intellectual works, and one can sense that there are among them deep connections in their disposition and numerous possibilities of communicating that are based on the same way of thinking and of feeling. The Jewish child is already aware of these differences as soon as it starts school. Jewish children feel the resentment that grows out of an instinctive suspicion of their strangeness that naturally is often met with a closing of the ranks. [***] [Jews] are the target of instinctive resentment because they are of a different tribe than the majority of the population."—A. Einstein, English translation by A. Engel, The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Volume 7, Document 35, Princeton University Press, (2002), pp. 156-157.

Albert Einstein often referred to Jews as "tribesmen" and Jewry as the "tribe". Fellow German Jew Fritz Haber was outraged at Albert Einstein's racist treachery and disloyalty. Einstein confirmed that he was disloyal and a racist, and was obligated,

"[. . .] to step in for my persecuted and morally depressed fellow tribesmen, as far as this lies within my power[.]"—A. Einstein quoted in: H. Gutfreund, "Albert Einstein and the Hebrew University", J. Renn, Editor, Albert Einstein Chief Engineer of the Universe: One Hundred Authors for Einstein, Wiley-VCH, Berlin, (2005), pp. 314-318, at 316.

Einstein bore no such loyalty to Germans, who had fed him and made him famous. In fact, Einstein wanted to exterminate Gentile Germans.

In a draft letter of 3 April 1920, Einstein wrote that children are conscious of "racial characteristics" and that this alleged "racial" gulf between children results in conflicts, which instill a sense of foreigness in the persecuted child. Einstein wrote,

"Unter den Kindern war besonders in der Volksschule der Antisemitismus lebendig. Er gruendete ich auf die den Kindern merkwuerdig bewussten Rassenmerkmale und auf Eindruecke im Religionsunterricht. Thaetliche Angriffe und Beschimpfungen auf dem Schulwege waren haeufig, aber meist nicht gar zu boesartig. Sie genuegten immerhin, um ein lebhaftes Gefuehl des Fremdseins schon im Kinde zu befestigen."—Letter from A. Einstein to P. Nathan of 3 April 1920, The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Volume 9, Document 366, Princeton University Press, (2004), p. 492. Also: The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Volume 1, Princeton University Press, (1987), p. lx, note 44.

Like Adolf Stoecker before him, [See: P. W. Massing, Rehearsal for Destruction: A Study of Political Anti-Semitism in Imperial Germany, Howard Fertig, New York, (1967), pp. 278-294.] Albert Einstein advocated the segregation of Jewish students. Peter A. Bucky quoted Albert Einstein,

"I think that Jewish students should have their own student societies. [***] One way that it won't be solved is for Jewish people to take on Christian fashions and manners. [***] In this way, it is entirely possible to be a civilized person, a good citizen, and at the same time be a faithful Jew who loves his race and honors his fathers."—P. A. Bucky, Einstein, and A. G. Weakland, The Private Albert Einstein, Andrews and McMeel, Kansas City, (1992), p. 88.

Einstein also stated,

"We must be conscious of our alien race and draw the logical conclusions from it. [***] We must have our own students' societies and adopt an attitude of courteous but consistent reserve to the Gentiles. [***] It is possible to be [***] a faithful Jew who loves his race and honours his fathers."—A. Einstein, The World As I See It, Citadel, New York, (1993), pp. 107-108.

Einstein had a reputation as a rabid anti-assimilationist. He was an ardent Jewish segregationist. Here again Einstein merely parroted the racist anti-assmilationism of his Zionist predecessors, like Solomon Schechter who dreaded assimilation more than pogroms—and one notes that Zionists encouraged pogroms in order to discourage assimilation.

Others repeated Theodor Herzl's theme, that Jews could not assimilate, because the presence of Jews in a host nation ultimately led to anti-Semitism due to Jewish parasitism—according to Herzl. Hilaire Belloc was a strong advocate of the view that Jews should not integrate. Belloc published a book on the subject entitled The Jews in 1922, and expressed similar convictions in G. K.'s Weekly in the 1930's. Belloc wrote biographies of men who had fallen under the influence of Zionists, like Oliver Cromwell and Napoleon. Belloc, however, was strongly opposed to Nazism. Douglas Reed took a similar Zionist stance on the alleged unassimilability of Jews in the late 1930's, though he later opposed Zionism. [See: D. Reed, Disgrace Abounding, Jonathan Cape, London, (1939).]

Racist Zionist Solomon Schecter stated, in harmony with numerous political Zionists, though in opposition to the vast majority of Jews,

"It is this kind of assimilation [the death of a "race" through integration], with the terrible consequences indicated, that I dread most; even more than pogroms."—S. Schechter, Zionism: A Statement, Federation of American Zionists, New York, (1906); reprinted in the relevant part in A. Hertzberg, The Zionist Idea, Harper Torchbooks, New York, (1959), p. 507.

On 15 March 1921, Kurt Blumenfeld wrote to Chaim Weizmann,

"Einstein [***] is interested in our cause most strongly because of his revulsion from assimilatory Jewry."—J. Stachel, Einstein from 'B' to 'Z', Birkhaeuser, Boston, (2002), p. 79, note 41.

Einstein stated in 1921,

"To deny the Jew's nationality in the Diaspora is, indeed, deplorable. If one adopts the point of view of confining Jewish ethnical nationalism to Palestine, then one, to all intents and purposes, denies the existence of a Jewish people. In that case one should have the courage to carry through, in the quickest and most complete manner, entire assimilation. We live in a time of intense and perhaps exaggerated nationalism. But my Zionism does not exclude in me cosmopolitan views. I believe in the actuality of Jewish nationality, and I believe that every Jew has duties towards his coreligionists. [***] [T]he principal point is that Zionism must tend to strengthen the dignity and self-respect of the Jews in the Diaspora. I have always been annoyed by the undignified assimilationist cravings and strivings which I have observed in so many of my friends."—A. Einstein, "Jewish Nationalism and Anti-Semitism", The Jewish Chronicle, (17 June 1921), p. 16.

In 1921, Einstein declared, referring to Eastern European Jews,

"These men and women retain a healthy national feeling; it has not yet been destroyed by the process of atomisation and dispersion."—J. Stachel, "Einstein's Jewish Identity", Einstein from 'B' to 'Z', Birkhaeuser, Boston, (2002), p. 65. Stachel cites, About Zionism: Speeches and Letters, Macmillan, New York, (1931), pp. 48-49. For Zionist Ha-Am's use of the image of atomisation and dispersion, see: A. Hertzberg, The Zionist Idea, Harper Torchbooks, New York, (1959), p. 276.

On 1 July 1921, Einstein was quoted in the Juedische Rundshau on page 371,

"Let us take brief look at the development of German Jews over the last hundred years. With few exceptions, one hundred years ago our forefathers still lived in the Ghetto. They were poor and separated from the Gentiles by a wall of religious tradition, secular lifestyles and statutory confinement and were confined in their spiritual development to their own literature, only relatively weakly influenced by the forceful progress which intellectual life in Europe had undergone in the Renaissance. However, these little noticed, modestly living people had one thing over us: Every one of them belonged with all his heart to a community, into which he was incorporated, in which he felt a worthwhile member, in which nothing was asked of him which conflicted with his normal processes of thought. Our forefathers of that era were pretty pathetic both bodily and spiritually, but—in social relations—in an enviable state of mental equilibrium. Then came emancipation. It offered undreamt of opportunities for advancement. The isolated individual quickly found their way into the upper financial and social circles of society. They eagerly absorbed the great achievements of art and science which the Occidentals had created. They contributed to the development with passionate affection, and themselves made contributions of lasting value. They thereby took on the lifestyle of the Gentile world, turning away from their religious and social traditions in growing masses—took on Gentile customs, manners and mentality. It appeared as if they were being completely dissolved into the numerically superior, politically and culturally better organized host peoples, such that no trace of them would be left after a few generations. The complete eradication of the Jewish nationality in Middle and Western Europe appeared to be inevitable. However, it didn't turn out that way. It appears that racially distinct nations have instincts which work against interbreeding. The adaptation of the Jews to the European peoples among whom they have lived in language, customs and indeed even partially in religious practices was unable to eliminate all feelings of foreigness which exist between Jews and their European host peoples. In short, this spontaneous feeling of foreigness is ultimately due to a loss of energy. For this reason, not even well-meant arguments can eradicate it. Nationalities do not want to be mixed together, rather they want to go their own separate ways. A state of peace can only be achieved by mutual tolerance and respect."—

Einstein stated that Jews should not participate in the German Government,

"I regretted the fact that [Rathenau] became a Minister. In view of the attitude which large numbers of the educated classes in Germany assume towards the Jews, I have always thought that their natural conduct in public should be one of proud reserve."—R. W. Clarck, Einstein, the Life and Times, World Publishing Company, USA, (1971), p. 292. Clarck refers to: Neue Rundschau, Volume 33, Part 2, pp. 815-816.

Einstein merely parroted the Zionist Party line. Werner E. Mosse wrote,

"While the leaders of the CV saw it as their special duty to represent the interests of the German Jews in the active political struggle, Zionism stood for. . . systematic Jewish non-participation in German public life. It rejected as a matter of principle any participation in the struggle led by the CV."—W. E. Mosse, "Die Niedergang der deutschen Republik und die Juden", The Crucial Year 1932, p. 38; English translation in: K. Polkehn, "The Secret Contacts: Zionism and Nazi Germany, 1933-1941", Journal of Palestine Studies, Volume 5, Number 3/4, (Spring-Summer, 1976), pp. 54-82, at 56-57.

In 1925, Einstein wrote in the official Zionist organ Juedische Rundschau,

"By study of their past, by a better understanding of the spirit [Geist] that accords with their race, they must learn to know anew the mission that they are capable of fulfilling. [***] What one must be thankful to Zionism for is the fact that it is the only movement that has given many Jews a justified pride, that it has once again given a despairing race the necessary faith, if I may so express myself, given new flesh to an exhausted people."—English translation by John Stachel in J. Stachel, "Einstein's Jewish Identity", Einstein from 'B' to 'Z', Birkhaeuser, Boston, (2002), p. 67. Stachel cites, "Botschaft", Juedische Rundschau, Volume 30, (1925), p. 129; French translation, La Revue Juive, Volume 1, (1925), pp. 14-16.

On 12 October 1929, Albert Einstein wrote to the Manchester Guardian,

"In the re-establishment of the Jewish nation in the ancient home of the race, where Jewish spiritual values could again be developed in a Jewish atmosphere, the most enlightened representatives of Jewish individuality see the essential preliminary to the regeneration of the race and the setting free of its spiritual creativeness."—J. Stachel, "Einstein's Jewish Identity", Einstein from 'B' to 'Z', Birkhaeuser, Boston, (2002), p. 65. Stachel cites, About Zionism: Speeches and Letters, Macmillan, New York, (1931), pp. 78-79.

Einstein's public racism eventually waned, but he continued to publicly express his segregationist philosophy in the same terms as anti-Semites, as well as his belief that Jews "thrived on" and owed their "continued existence" to anti-Semitism. Einstein stated in December of 1930 to an American audience,

"There is something indefinable which holds the Jews together. Race does not make much for solidarity. Here in America you have many races, and yet you have the solidarity. Race is not the cause of the Jews' solidarity, nor is their religion. It is something else—which is indefinable."—A. Einstein quoted in "Einstein on Arrival Braves Limelight for Only 15 Minutes", The New York Times, (12 December 1930), pp. 1, 16, at 16.

Einstein's confusing public statement perhaps resulted from his desire to promote multi-culturalism in America, which had the benefit of freeing up Jewish immigration to the United States. [See: E. A. Ross, The Old World in the New: The Significance of past and Present Immigration to the American People, Century Company, New York, (1914), p. 144.] Einstein was also likely parroting, or trying to parrot, a fellow anti-assimilationist political Zionist whose pamphlet was well known in America, Solomon Schechter and his Zionism: A Statement, Federation of American Zionists, New York, (1906), in which Schechter states, among other things,

"Zionism is an ideal, and as such is indefinable."—Reprinted in the relevant part in A. Hertzberg, The Zionist Idea, Harper Torchbooks, New York, (1959), p. 505.

Einstein avowed, circa 3 April 1920, that,

"If what anti-Semites claim were true, then indeed there would be nothing weaker, more wretched, and unfit for life, than the German people"—A. Einstein, English translation by A. Engel, The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Volume 7, Document 35, Princeton University Press, (2002), pp. 156-157.

Einstein often avowed that the anti-Semites' beliefs were true, and, hence, Einstein wished the Germans dead. When discussing the meaning of life, Einstein spoke to Peter A. Bucky about persons and creatures who "[do] not deserve to be in our world" and are "hardly fit for life." [P. A. Bucky, Einstein, and A. G. Weakland, The Private Albert Einstein, Andrews and McMeel, Kansas City, (1992), p. 111.]

Einstein's language is quite similar to the language of Hitler's "T4" "Euthanasia-Programme".

After siding with Germany's enemies in the First World War—while living in Germany, and after intentionally provoking Germans into increased anti-Semitism, which he thought was good for Jews, and after defaming German Nobel Prize laureates in the international press to the point where they felt obliged to join Hitler's cause, which cause eventually resulted in the genocide of Europe's Jews; Einstein sponsored the production of genocidal weapons to mass murder Germans, whom he had hated all of his life, in the famous letter to President Roosevelt that Einstein signed urging Roosevelt to begin the development of atomic bombs—before the mass murder of Jews had begun. [Cf. A. Unsoeld, "Albert Einstein — Ein Jahr danach", Physikalische Blaetter, Volume 36, (1980), pp.337-339; and Volume 37, Number 7, (1981), p. 229.]

Einstein callously asserted that the use of atomic bombs on civilian populations was "morally justified". I quote Einstein without delving into the question of who first bombed civilian centers,

"It should not be forgotten that the atomic bomb was made in this country as a preventive measure; it was to head off its use by the Germans, if they discovered it. The bombing of civilian centers was initiated by the Germans and adopted by the Japanese. To it the Allies responded in kind—as it turned out, with greater effectiveness—and they were morally justified in doing so."—A. Einstein, "Atomic War or Peace", Atlantic Monthly, (November, 1945, and November 1947); as reprinted in: A. Einstein, Ideas and Opinions, Crown, New York, (1954), p. 125.

Einstein advocated genocidal collective punishment,

"The Germans as an entire people are responsible for these mass murders and must be punished as a people if there is justice in the world and if the consciousness of collective responsibility in the nations is not to perish from the earth entirely."—A. Einstein, "To the Heroes of the Battle of the Warsaw Ghetto", Bulletin of the Society of Polish Jews, New York, (1944), reprinted in Ideas and Opinions, Crown, New York, (1954), pp. 212-213.

Einstein also stated,

"It is possible either to destroy the German people or keep them suppressed; it is not possible to educate them to think and act along democratic lines in the foreseeable future."—A. Einstein, quoted in O. Nathan and H. Norton, Einstein on Peace, Avenel Books, New York, (1981), p. 331.

Albrecht Foelsing has assembled a compilation of post-WW II quotations from Einstein, which evince Einstein's lifelong habit of stereotyping people based on their ethnicity. Einstein expressed his hatred to Max Born,

"With the Germans having murdered my Jewish brethren in Europe, I do not wish to have anything more to do with Germans, not even with a relatively harmless Academy. [***] The crimes of the Germans are really the most hideous that the history of the so-called civilized nations has to show. [***] [It was] evident that a proud Jew no longer wishes to be connected with any kind of German official event or institution. [***] After the mass murder committed by the Germans against my Jewish brethren I do not wish any publications of mine to appear in Germany."—A. Einstein quoted in A. Foelsing, Albert Einstein: A Biography, Viking, New York, (1997), pp. 727-728.

Einstein wrote to Born on 15 September 1950 that his views towards Germans predated the Nazi period,

"I have not changed my attitude to the Germans, which, by the way, dates not just from the Nazi period. All human beings are more or less the same from birth. The Germans, however, have a far more dangerous tradition than any of the other so-called civilized nations. The present behavior of these other nations towards the Germans merely proves to me how little human beings learn even from their most painful experiences."—A. Einstein quoted in M. Born, The Born-Einstein Letters, Walker and Company, New York, (1971), p. 189.

On learning that Born would return to Germany, Einstein wrote on 12 October 1953,

"If anyone can be held responsible for the fact that you are migrating back to the land of the mass-murderers of our kinsmen, it is certainly your adopted fatherland — universally notorious for its parsimony."—A. Einstein quoted in M. Born, The Born-Einstein Letters, Walker and Company, New York, (1971), p. 199.

Einstein's statements and those of other like-minded racist Zionists threw fuel on the fire of Nazi Zionism, which was begun and ruled by crypto-Jews. The Einsteinian Zionist promotion of anti-Semitism is reflective of the spirit and tone enunciated in the Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion, Number 9, which states,

"Nowadays, if any States raise a protest against us, it is only pro forma at our discretion, and by our direction, for their anti-Semitism is indispensable to us, for the management of our lesser brethren."—L. Fry, Waters Flowing Eastward: The War Against the Kingship of Christ, TBR Books, Washington, D. C., (2000), p. 137.

Christopher Jon Bjerknes

More on Einstein's racism can be found in my book The Manufacture and Sale of Saint Einstein

Related:

Albert Einstein: Plagiarist of the Century

Einstein Incorrigible Plagiarist

A theory of Einstein the irrational plagiarist

The genius... that wasn't! Albert Einstein: A Jewish Myth

Albert Einstein a thief, a liar and a plagiarist

![[Image6.jpg]](http://bp0.blogger.com/_s5yaZ0Ye2Mo/R0b5CDuw-RI/AAAAAAAAFm8/zUzRnUYynsE/s1600/Image6.jpg)

![[Zionazis-1.jpg]](http://1.bp.blogspot.com/_s5yaZ0Ye2Mo/SYIx9LEISSI/AAAAAAAASO0/BY5Y5A_FQ_4/s1600/Zionazis-1.jpg)